Diesel Trade

Between 2000 and 2019 (average data for the first three quarters), U.S. diesel demand grew at an average rate of 0.5% per year. As noted above, refinery production of diesel grew at an average rate of 1.9% per year. The net result has been that U.S. imports of diesel have fallen, and exports have risen.

Canada has been a significant international source, and it also has been the only stable source of imports. Imports of Canadian diesel grew from approximately 60,000 bpd in 1993 to over 100,000 bpd in 2002, and imports typically have remained the 100,000 – 140,000-bpd range since then. In the 1990s and 2000s, imports from Venezuela and the U.S. Virgin Islands were common. Diesel imports from Venezuela typically averaged 50,000 – 60,000 bpd. Diesel imports from the St. Croix refinery in the U.S. Virgin Islands were usually in the range of 60,000 – 100,000 bpd. Unrest in Venezuela and deteriorating relations with the U.S. cut exports nearly to zero. Exports to the U.S. from the Virgin Islands vanished entirely when the refinery there shut down in 2012. This refinery is scheduled to be reopened in 2020 at partial capacity, hoping to benefit from the collapse of Venezuelan refining and from the adoption of IMO 2020 marine fuels.

U.S. imports of diesel had been trending up from 1993 until the collapse of the Great Recession in 2008 – 2009. In 1993, diesel imports averaged 184,000 bpd, growing to over 300,000 bpd during the 2003 – 2007 period. The Great Recession caused U.S. total fuel demand to fall sharply. Between 2007 and 2009, the EIA reported that demand for finished petroleum products dropped by 1.776 mmbpd, including 0.565 mmbpd of diesel. Demand began to recover after 2009, but U.S. imports of diesel continued to decline. Imports fell below 200,000 bpd in the year 2011, and they have remained below that threshold ever since. The key force behind this was the Shale Boom, which greatly boosted domestic oil supply and cut into the need for imports.

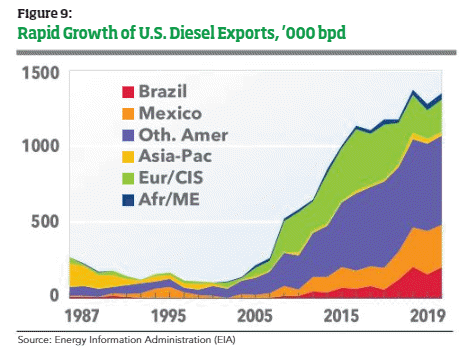

The drop in diesel imports was accompanied by an even more spectacular rise in exports. Figure 9 displays the growth in U.S. diesel exports and the diversification of foreign markets. Between 1993 and 2005, U.S. diesel exports had slowly dwindled, falling from 272,000 bpd in 1993 to 138,000 bpd in 2005. After 2005, however, exports began to surge, first passing the million-barrel-per-day mark in 2012 and then continuing to rise to an average of 1.347 mmbpd in the first three quarters of 2019. This equates to an incredible growth rate of 17.7% per year.

The Asia-Pacific region historically was a key outlet for U.S. diesel, but its role has diminished. In 1993, the U.S. exported 155,000 bpd of diesel to the Asia-Pacific region. This nearly vanished in the 2004 – 2007 period, but exports recovered modestly to 27,000 bpd in 2018. The main growth has been in export markets closer to home. Currently, approximately 80% of U.S. diesel exports are sent to countries in the Americas and the Caribbean. Brazil and Mexico in particular have grown into major markets, with Brazil importing 202,700 bpd and Mexico importing 284,000 bpd during the first three quarters of 2019. The U.S. is now sending diesel to nearly every importing country in the Western Hemisphere, including Chile, Peru, Panama, Colombia, Guatemala, Argentina, the Bahamas, Canada, Ecuador, the Dominican Republic and El Salvador. Exports to Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) also expanded quickly, soaring from 16,000 bpd in 2005 to 216,000 bpd during the first three quarters of 2019. Some of the key markets are the Netherlands, Spain, the United Kingdom, France and Gibraltar.

Conclusion

The U.S. diesel market has changed significantly in recent years. The quest for higher-quality, lower-emission diesel necessitated a decades-long program of refinery investment that phased out high-sulfur grades in favor of medium-sulfur grades, then phased out medium-sulfur grades in favor of ultra-low-sulfur grades. It also expanded the volumetric output of diesel at a rate that far surpassed the growth in domestic demand. The U.S. has emerged as the Western Hemisphere’s dominant exporter of diesel, currently providing 1.347 million barrels per day of diesel to export markets. Some of these markets lack large, sophisticated refineries, and the U.S. is a key source of low-sulfur diesel for them. The fact that U.S. refineries produce ample supplies of high-quality diesel keeps a lid on domestic prices.

Compared to much of the developed world, diesel remains a bargain in the U.S. For most of 2019, retail prices were below their 2018 levels. The U.S. tax burden on diesel of 18.2% is modest compared to the 61.2% assessed in the U.K. In November 2019, the average retail price of diesel in the U.S. was $3.19/gallon, whereas it was above $5/gallon in Spain and Germany, and it was over $6/gallon in the U.K., Italy and France.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration forecasts that gasoline will remain the dominant fuel in the U.S. transport sector through the year 2050, but that diesel’s relative role in the fuel mix will grow. Volumetric demand for both fuels is forecast to decline, posing challenges to the fuels industry. The rate of decline for diesel is forecast to be more moderate. There are many experts who believe oil demand will, and must, peak and begin to fall much sooner than currently forecast. The past thirty years have brought enormous change to the diesel market. The next thirty could bring even more momentous change. It seems safe to say that transport demand and the role of trucks will increase, regardless of the fuel they use, and that in the near term, that fuel will be mainly diesel. In the long term, anything is possible.

Editor’s Note: This article is adapted from one appearing in the U.K.-based International Journal of Hydrocarbon Engineering.