Excerpted from This Week in Petroleum

Release date: September 18, 2019

On Saturday, September 14, 2019, an attack damaged the Saudi Aramco Abqaiq oil processing facility and the Khurais oil field in eastern Saudi Arabia. The Abqaiq oil processing facility is the world’s largest crude oil processing and stabilization plant with a capacity of 7 million barrels per day (b/d), equivalent to about 7% of global crude oil production capacity. On Monday, September 16, 2019, the first full day of trading after the attack, Brent and West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil prices experienced the largest single day price increase since August 21, 2008 and June 29, 2012, respectively.

On Tuesday, September 17, Saudi Aramco reported that Abqaiq was producing 2 million b/d and that its entire output capacity was expected to be fully restored by the end of September. Additionally, Saudi Aramco stated that crude oil exports to customers will continue by drawing on existing inventories and offering additional crude oil production from other fields. Tanker loading estimates from third-party data sources indicate that loadings at two Saudi Arabian export facilities were restored to the pre-attack levels. Likely driven by news of the expected return of the lost production capacity both Brent and WTI crude oil prices fell on Tuesday, September 17.

Crude oil markets will certainly continue to react to new information as it becomes available in the days and weeks ahead, but this disruption and the resulting changes in global crude oil prices will influence U.S. retail gasoline prices.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates that Saudi Arabia was producing 9.9 million b/d of crude oil in August, and estimates from the Joint Organizations Data Initiative (JODI) indicate the country exported 6.9 million b/d during July, the latest month for which data are available (Figure 1). Estimates from a third-party tanker tracking data service, ClipperData, indicate Saudi Arabian crude oil exports in August remained at 6.7 million b/d. These crude oil production and export levels are each 0.5 million b/d lower than their respective 2018 annual averages. JODI data indicate that Saudi Arabia held nearly 180 million barrels of crude oil in inventory at the end of July 2019. Saudi Arabia can use these inventories to maintain a similar level of crude oil exports as before the strike, assuming the production outage is short in duration, as indicated by Saudi Aramco’s update on September 17.

Saudi Arabia is rare among oil producing countries, in that it regularly maintains spare crude oil production capacity as a matter of its oil production policy. EIA defines spare capacity as the volume of production that can be brought online within 30 days and sustained for at least 90 days using sound business practices. In the September Short-Term Energy Outlook (STEO) EIA estimated that the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) spare capacity was 2.2 million b/d in August 2019, nearly all of which was in Saudi Arabia. Outside of OPEC, EIA does not include any unused capacity in its spare capacity total, even when countries periodically hold such capacity (as is the case with Russia). During previous periods of significant oil supply disruptions, Saudi Arabia generally increased production to offset the loss of supplies and stabilize markets (Figure 2).

Following the September 14 attack and ensuing outage at the Abqaiq facility, the amount of available spare capacity that can be brought online within 30 days in Saudi Arabia is unknown. In addition, because Saudi Arabia holds most of OPEC’s spare capacity, there is likely little spare production capacity elsewhere to offset the loss. Russia may be able to increase production in response to a disruption and higher prices, but the amount of time needed for these volumes to become available is uncertain. The United States would also likely be able to increase production, but it would take longer than 30 days. Therefore, without Saudi Arabian spare capacity the global crude oil market is vulnerable to production outages, as events would be more disruptive than normal.

The most readily available alternative source of supply during a supply outage is stocks of crude oil. As of September 1, commercial inventories of crude oil and other liquids for Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) members were estimated at 2.9 billion barrels, enough to cover 61 days of its members’ liquid fuels consumption. On a days-of-supply basis, OECD commercial inventories are 2% lower than the five-year (2014-18) average (Figure 3).

The United States has two types of crude oil inventories: those that private firms hold for commercial purposes, and those the federal government holds in the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) for use during periods of major supply interruption. Weekly data for September 13 indicate total U.S. commercial inventories were equivalent to 24 days of current U.S. refinery crude oil inputs, with the SPR holding additional volumes equal to slightly more than 37 additional days of current refinery inputs, for a total of 62 days. The supply coverage provided by oil inventories can also be measured by days of net crude oil imports (imports minus exports). By this metric, as of June 2019 the United States could meet its net import needs by drawing down the SPR for 162 days. The Energy Policy and Conservation Act states the President may make the decision to withdraw crude oil from the SPR should they find that there is a severe petroleum supply disruption. The SPR has been used in this capacity three times since its creation: first, in 1991 at the beginning of Operation Desert Storm; second, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in September 2005; and third, in June 2011 to help offset crude oil supply disruptions in Libya.

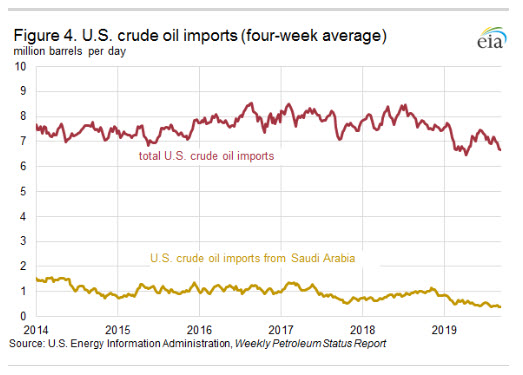

Although U.S. imports of crude oil from Saudi Arabia have declined during the past three years—and recently hit a four-week average record low of 380,000 b/d in the week ending September 6—the United States still imports about 7 million b/d of crude oil (Figure 4). As a result, a tighter global crude oil market and increased global crude oil prices will ultimately increase the price of crude oil and transportation fuels in the United States.

Crude oil prices are the largest determinant of the retail price for gasoline, the most widely consumed transportation fuel in the United States. In general, because gasoline taxes and retail distribution costs are generally stable, movements in U.S. gasoline prices are primarily the result of changes in crude oil prices and wholesale margins. Each dollar per barrel of sustained price change in crude oil translates to an average change of about 2.4 cents/gal in petroleum product prices. About 50% of a crude oil price change passes through to retail gasoline prices within two weeks and 80% within four weeks. However, this price pass-through tends to be more rapid when crude oil prices increase than when they decrease. Brent crude oil prices are more relevant than WTI prices in determining U.S. retail gasoline prices.