By Keith Reid

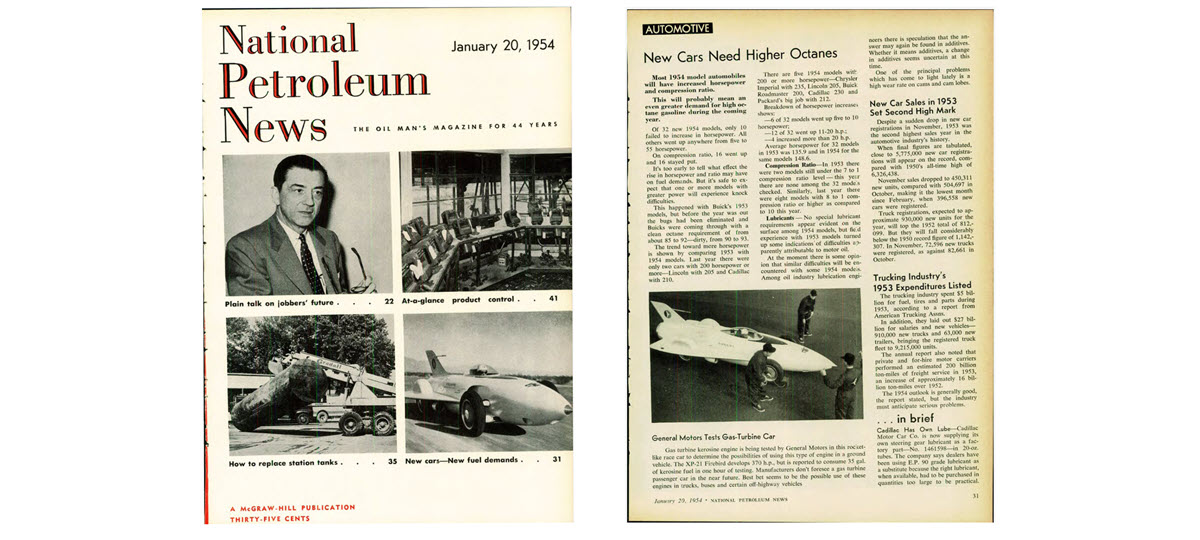

Octane has also been critically important for automobiles. National Petroleum News (NPN) articles from the 1920s and ’30s regularly covered fuel quality and octane with the rise of higher performing, higher compression engines. Octane was still an issue as the 1950s arrived, as illustrated by the article “New Cars Need Higher Octanes” in the January 20, 1954, issue.

Octane ratings are basically the pressure at which a fuel will spontaneously combust instead of normally combust, so higher compression engines require higher octane ratings or the “knock” caused by spontaneous combustion can damage the engine.

As the NPN article noted “…most 1954 model automobiles will have increased horsepower and compression ratio. This will probably mean an even greater demand for high octane gasoline during the coming year. Of 32 new 1954 models, only 10 failed to increase in horsepower. All others went up anywhere from 5 to 55 horsepower. On compression ratio, 16 went up and 16 stayed put.”

Compression rations had moved up from a high of 7:1 in 1953 to 8:1 in 1954.

While it was too early to determine what effect the rise in horsepower and compression ratios might have on fuel performance, it was anticipated that one or more models would experience knock difficulties, noting something similar happened with Buick’s 1953 models. To some extent, it wasn’t just the fuel but how the engine was tuned, and those Buicks that needed 90 to 93 octanes to run smoothly were eventually able to achieve the same result with octane ratings between 85 and 92.

Going back to the early octane issue days, various brands had developed some form of “super” high octane offer. By the early 1950s it was common to find two grades of gasoline, a regular and a premium, with octane somewhere around 79 for regular and 85 for premium.

Offering a more exotic, much higher octane as a “racing fuel” was also not new (and is still a market opportunity today), helped by motorists who bought the fuel for some extra “pep” without knowing it only provided that pep in highly modified, extra high-compression engines

It’s interesting to look back at this early stage of the “hot rod” golden era (1950s to the pre-Arab oil embargo in the early 1970s). The average horsepower for 32 models in 1953 was 135.9, and in 1954 it was 148.6 for the same models. Five models were cited as pushing past the 200-horsepower mark with the Chrysler Imperial at 235, Lincoln at 205, Buick Roadmaster at 200, Cadillac at 230 and a Packard with 212.

Today, the average horsepower is in the 180 to 240 range according to Autolist, and some models are as much as 400 to 700 horsepower. Compression can average between 8:1 and 14.7:1 and octane between 89 and 94.

Today’s octane ratings are in line with those of the late 1950s, but modern compression engines perform well without knock concerns. A key advancement has been the arrival of digital sensors and computers with sophisticated ignitions to keep knock under control. In fact, these vehicles can run regular or midgrade if required, although with some loss of performance and efficiency.

Keith Reid is the editor of Fuels Market News. He can be reached at [email protected].

Keith Reid is the editor of Fuels Market News. He can be reached at [email protected].