By Dr. Nancy Yamaguchi

Our world has experienced several oil shocks, but the shock caused by the coronavirus outbreak in early 2020 has been unlike any other in scale, speed, impact and response. In the absence of vaccines and proven disease treatments, social distancing and stay-at-home orders are the main weapons available to fight COVID-19. On March 19, 2020, California became the first state to launch mandatory shelter-in-place orders. By the end of March, 36 other states had joined California. Five additional states followed during the first week of April. Discretionary travel largely vanished. Large events such as concerts and sports competitions were canceled. Students stayed home and took classes online. Restaurants, bars and most retail outlets were closed. Fuel demand collapsed, as did fuel prices.

As this article is posted, the COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, but there are signs that the U.S. is succeeding in “flattening the curve,” that is, decreasing and delaying the epidemic peak to slow the infection rate and prevent health-care services from being overwhelmed. The groundwork has been laid for a phased re-opening of the economy. This article focuses on how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected fuel demand and employment.

COVID-19 Causes a Fuel Demand Collapse

Measuring fuel consumption is imprecise, but the timeliest data available to the public is the official data published by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). The EIA publishes weekly “product supplied” data, which is the proxy for demand because it measures the disappearance of fuel from primary sources.[1] Unless otherwise noted, the time series charts presented here focus on the 11 weeks between March 13 and May 22, 2020.

The EIA data extend back to November 1990. At that time, total U.S. oil product demand amounted to approximately 16.6 million barrels per day (mmbpd.) The Great Recession of 2008–09 caused a dramatic contraction of demand. Between 2013 and 2019, demand began to grow again. The COVID-19 pandemic caused the fastest, sharpest drop in demand since the EIA started reporting the data. Indeed, demand in the first three weeks of April 2020 was the lowest in the data series. The next-lowest demand levels recorded were back in 1992.

COVID-19 Impact on Gasoline Demand

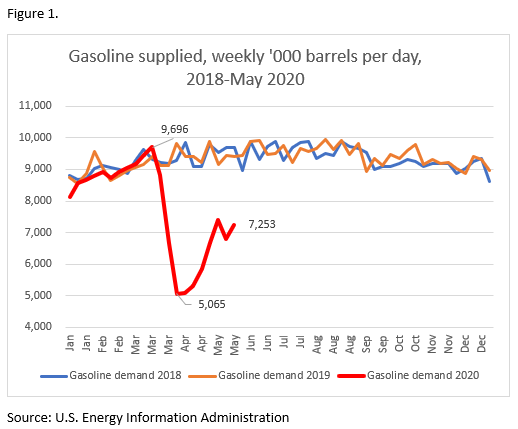

Figure 1 presents EIA data on gasoline demand in 2018, 2019 and 2020 (January-May.) The data show seasonality in demand, with demand rising in spring and summer and trailing down in autumn and winter. In 2018 and 2019, spring and summer demand typically was in the 9.2-9.9 mmbpd range, while autumn and winter demand ebbed to the 8.6-9.1 mmbpd range. In early 2020, gasoline demand appeared to be heading up for a strong driving season, reaching nearly 9.7 mmbpd by mid-March.

During the second half of March, however, 37 states launched stay-at-home orders, followed by five more states the first week of April.

Gasoline use plunged to 5.065 mmbpd during the week ended April 3. During the same week in 2019, demand had averaged 9.806 mmbpd, nearly twice as much. Demand recovered to 7.253 mmbpd by the week ended May 22. According to this data measurement, gasoline demand has recovered to 77% of what might be expected for this time of the year.

COVID-19 Impact on Diesel Demand

Figure 2 presents EIA data on diesel demand in 2018, 2019 and 2020 (January-May.) In 2018, demand averaged 4.146 mmbpd over the year. Demand declined to 4.082 mmbpd in 2019. The weekly data show demand ranging from approximately 3.2 mmbpd to 4.7 mmbpd. In early 2020, diesel demand started the year lower than in prior years, in part because the winter of 2019–20 was one of the warmest on record. Diesel supplied hovered around 4.0 mmbpd during the first quarter.

Diesel use fell to a low point of 3.164 mmbpd during the week ended April 24. This was approximately 75% of the demand seen during the same week in 2019 (4.215 mmbpd.) Diesel demand has moved up and down since then, recovering to nearly 3.7 mmbpd during the week ended May 15 before subsiding again below 3.3 mmbpd during the week ended May 22. According to this data measurement, diesel demand has recovered to 76% of what might be expected for this time of the year. COVID-19 has had a mixed impact on diesel demand, because while passenger travel in diesel-powered automobiles has fallen, the demand for freight transport has risen in many areas. This includes transport of medical supplies and rapid response to supply chain problems.

COVID-19 Impact on Jet Fuel Demand

While the COVID-19 pandemic is having a dramatic impact on gasoline and diesel demand, the impact on jet fuel demand has been staggering. According to industry group Airlines for America,[1] after seeing passenger volumes grow at approximately 5% in January to February 2020, air travel fell 89% in the week ended May 24. On March 26, Hawaii launched a mandatory 14-day quarantine period for passengers arriving from out of state. Travel to Hawaii fell to 97% year over year.

Figure 3 presents EIA data on jet fuel demand in 2018, 2019 and 2020 (January to May.) Demand averaged 1.707 mmbpd in 2018 and 1.74 mmbpd in 2019. In January and February 2020, jet fuel demand was on par with historic demand. By March, demand began to decline, and by April it had collapsed. At its low point in April, during the week ended April 10, jet fuel demand dropped to 0.463 mmbpd, just 28% of its level during the same week last year. Jet fuel demand is not clearly rebounding.

Figure 3 presents EIA data on jet fuel demand in 2018, 2019 and 2020 (January to May.) Demand averaged 1.707 mmbpd in 2018 and 1.74 mmbpd in 2019. In January and February 2020, jet fuel demand was on par with historic demand. By March, demand began to decline, and by April it had collapsed. At its low point in April, during the week ended April 10, jet fuel demand dropped to 0.463 mmbpd, just 28% of its level during the same week last year. Jet fuel demand is not clearly rebounding. It hit an even lower point of 0.352 mmbpd during the week ended May 8. This was a mere 20% of the demand level of 1.766 mmbpd seen during the same week one year before.

COVID-19 Causes Job Destruction

How quickly will fuel demand recover? Will it recover to its prior levels, or will the economy be changed forever? Will the low prices cause an uptick in demand, followed perhaps next year by a price spike because of lack of investment in energy? Will this be followed cyclically by another crash? These questions are critical to both buyers and sellers in the fuel market. But we remain in the midst of the event, and we cannot see the end. As to how the country will recover, the range of opinion is so wide that there is no accepted answer. One of the critical factors to watch, however, is unemployment. If jobs do not return, the economy cannot thrive.

The pandemic has caused massive destruction of jobs. Figure 4 presents the monthly unemployment rate in the U.S. between 2000 and April 2020, as reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).[1] At the height of the Great Recession, unemployment peaked at 10%. Coming out of this crisis, the U.S. began the longest period of economic expansion in history. As Figure 4 shows, the unemployment rate fell steadily until it hit lows of 3.5%-3.6% in 2019. These were the lowest rates of unemployment seen since 1969, five decades ago. The COVID-19 pandemic caused unemployment to skyrocket from 3.5% in February 2020 to 14.7% in April before retreating to 13.3% in May.

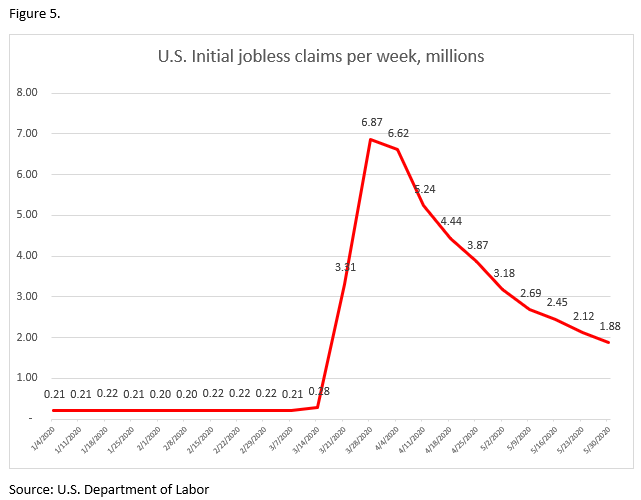

Figure 5 presents data from the U.S. Department of Labor showing how the COVID-19 crisis forced millions of people to file for unemployment benefits in just a few short weeks. The number of people filing initial jobless claims averaged 0.21 million per week in January and February. During the week of March 21, this number jumped to 3.31 million. At that time, five major states (California, Connecticut, Illinois, New Jersey and New York) had issued stay-at-home orders. By the next week, the number of initial jobless claims leapt to 6.87 million. At that point, 29 of the 50 states had launched stay-at-home orders. Within the next week, 42 states had instituted stay-at-home orders. The number of initial jobless claims was 6.62 million during the week ended April 4. For the next seven weeks the number of claims declined steadily. However, initial jobless claims remained in the millions. Over the 10-week period, a shocking total of 43.2 million people filed initial jobless claims.

Conclusion: An Unclear Path to Fuel Demand and Employment Recovery

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a severe oil market collapse. There are no proven effective treatments or vaccines for the disease. Economic activity was stifled as most of the population relied upon social distancing and shelter-in-place strategies. As this article is being written, the disease continues to spread and to take lives around the globe. For the time being, fuel prices are below their pre-COVID-19 levels, and a serious price rally is unlikely until demand picks up and overflowing inventories begin to be drained. Based on the latest product supplied data available, gasoline demand has recovered to approximately 74% of normal levels, diesel demand is at 87% of its expected level and jet fuel demand is at approximately 33% of its normal level. Economic recovery, and job recovery, will be the key determinant of the timing and strength of any demand recovery.

Dr. Yamaguchi is president of Trans-Energy Research Associates, a small, computer-oriented firm specializing in advanced analytical techniques in energy issues. She is a senior market analyst and contributing editor to FMN Media. Her work focuses on domestic and international energy markets, covering a wide spectrum of supply, demand, trade and pricing issues.

Dr. Yamaguchi is president of Trans-Energy Research Associates, a small, computer-oriented firm specializing in advanced analytical techniques in energy issues. She is a senior market analyst and contributing editor to FMN Media. Her work focuses on domestic and international energy markets, covering a wide spectrum of supply, demand, trade and pricing issues.

[1] https://www.eia.gov/tools/glossary/index.php?id=Product%20supplied

[2] https://www.airlines.org/dataset/impact-of-covid19-data-updates/#